When this residency began, the conversations began with forming a new coherent thought about mapping new ways to think about lost lovers and their love. It slowly morphed into a space where I could question my own thought process returning to the genealogy of the ongoing themes of my work.

Keeping in mind victims of violence, unidentified bodies, and unmarked graves, I began to understand the several ways I could make a restorative gesture where personhood was denied, brutally, glibly, to the humans in life and in death, in presence as in absence.

When fellow humans, the system, the state, fail us and our lovers and beloved, questions arise.

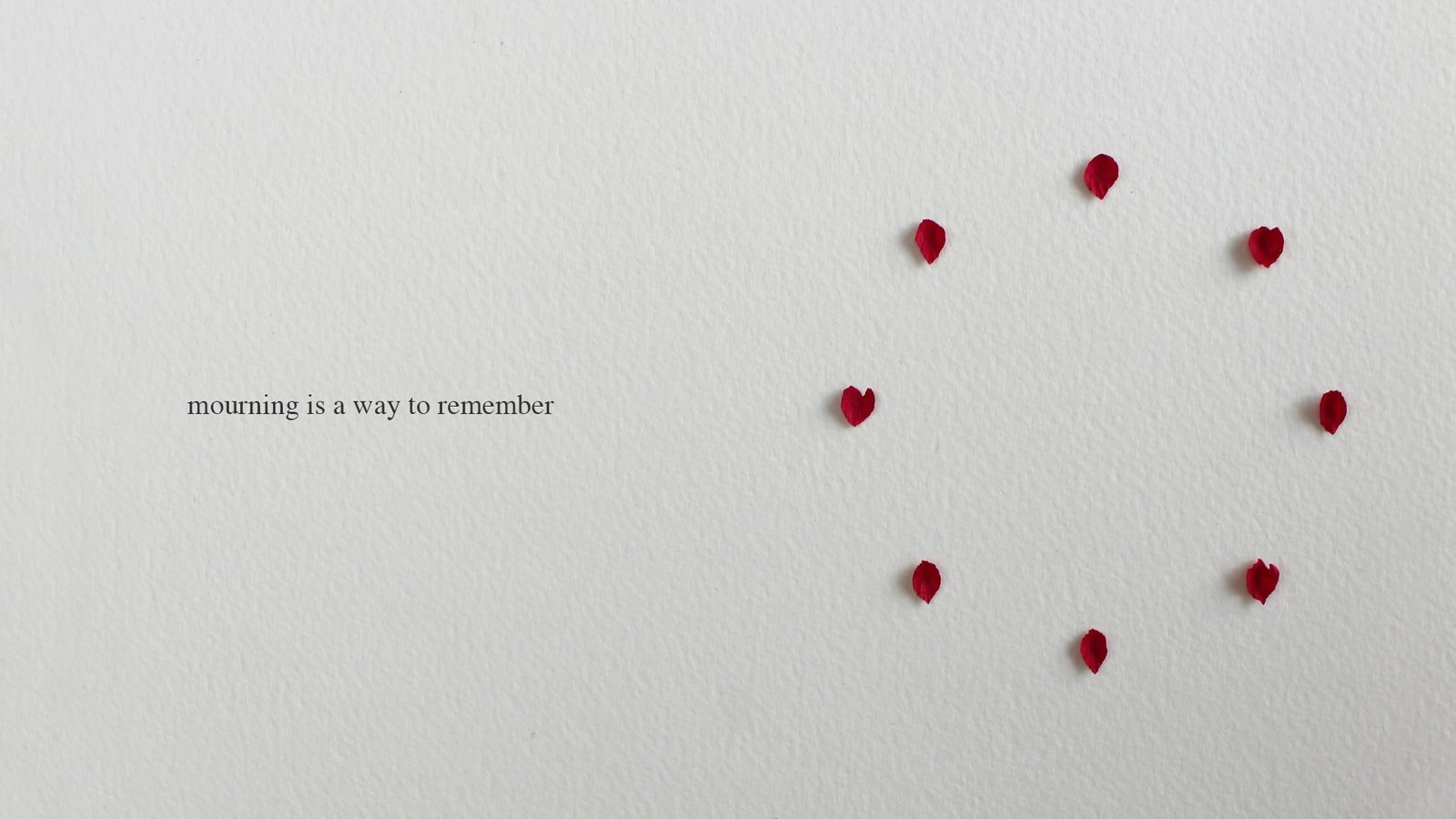

What does our memory mean to those who have wronged us? How do they remember what they have done? Can we send quiet reminders of the destruction they inflicted on so many lives? At the same time, the work found its way to this soft reminder for our lovers that exist without a body, to fumble through how to talk about them.